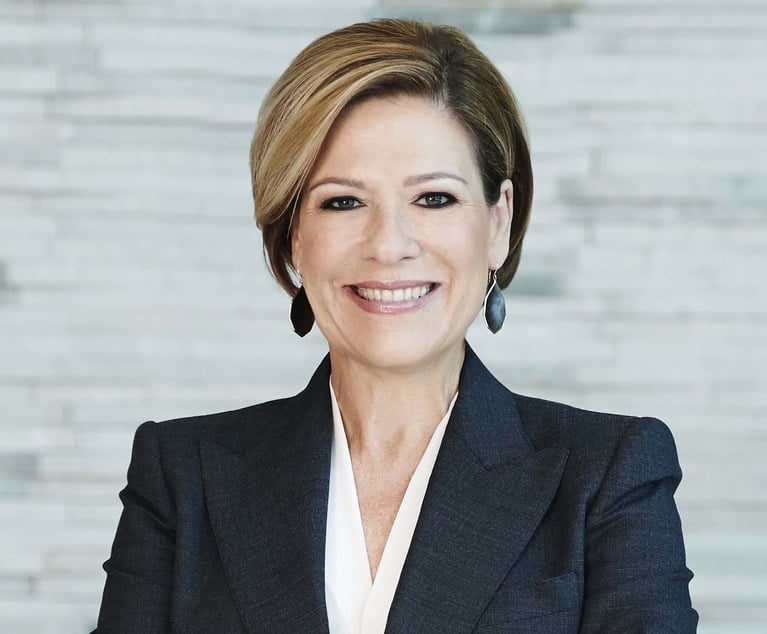

PALO ALTO, CA—With the recession beginning to become a memory of the past, the demand for housing is on the rise, and with it is the explosive interest in the multifamily market. That is according to Michael C. Polentz, co-chair of the real estate and land use practice group at Manatt, Phelps & Phillips LLP, located in the Palo Alto office. And according to Payvand Abghari, an associate in the real estate and land use practice group at Manatt, Phelps & Phillips LLP, located in the Orange County, CA office, “as more and more Americans are choosing to marry later and postponing having children, the market has seen a significant increase in one- and two-person households and a resulting decline in the demand for the higher square footage single family residence among Millennials.”

Enter the condominium: low-to-moderately priced housing in urban areas, where the average price of a home is out of reach for many, and where homeowners can build equity while still enjoying the luxury and convenience of on-site amenities (for a pro rata share in maintenance costs), they say. In the exclusive column below, the pair looks at condo demand, restrictive covenants and more.

The views expressed below are the author's own.

Condo Conversions in a Blooming Market

While the condo demand is high, it is especially so for condo conversions, since transforming an existing structure to individual condos is cheaper, quicker and generally less risky than building one from the ground up. A condominium conversion is the process whereby a piece of rental property, such as an existing apartment building, hotel or commercial property, is transformed from a property wholly owned by a single title holder to individual units put up for sale to the public. Aside from the product demand, attractive economic incentives are also driving land owner and developer-converters towards the condo conversion market. Conversions have been cited as a way for owners to turn a substantial profit. For developers, a conversion represents the opportunity to turn a quick profit, since the aggregate value of individual for-sale units far exceeds the value of the property when it is placed for sale as an apartment building.

Restrictive Covenants as a Shield against Litigation

Simultaneous with the increasing interest in condo conversions, the market is also seeing the growth of a certain breed of restrictive terms in modern purchase and sale agreements—those which strictly forbid any buyer from the thought of even considering a condo conversion. But why the red tape? Simply stated, these binding restrictions on the use of property, or “restrictive covenants”, can act as a shield against exposure to costly construction defect claims.

Take the following hypothetical: A New York-based developer wishes to purchase an apartment complex in California's leading Silicon Valley market. The property was built in 2010 and there are still five years remaining on California's 10-year statute of limitations for latent defects. The parties shake hands and close the deal, and after performing extensive renovations, the developer quickly moves to convert the property to individual for-sale condos. One year later, a lawsuit is filed against the developer on behalf of the owners, alleging major defects in the construction, and demanding millions of dollars in damages relating to high ticket issues like foundation, framing and water intrusion. As a result, the developer, or the “converter”, will demand indemnity from the original seller and its contractors as the original builders, while the seller and its contractors will point a finger at the converter, since it last performed copious renovations on the property and was last in the chain of title.

As a general matter, many of the same theories of liability are used in prosecuting construction defect claims for condo conversion projects as with new developments. Such claims include negligent conversion, general negligence, breach of warranties and typical breach of contract claims. To date, there is little to no case law establishing liability against a converter for strict liability if the converter did not create or alter the condition claimed to be defective, and did not have actual or constructive knowledge of the defects. However, construction defect plaintiffs frequently argue the converter is nonetheless at fault because it placed a mass-produced, defective product into the “stream of commerce”, a claim commonly seen in tort product liability cases involving the vertical distribution of defective goods. Thus, as cases involving condo conversions grow, so have the arguments that converters should be liable for damages relating to the whole property, not just the particular improvements they elect to undertake.

With the nationwide movement towards construction defect litigation, many have pushed state legislators to protect sellers, developers and contractors from construction defect liability, including the institution of various “Right to Repair” or “Notice and Opportunity to Cure” defect laws. However, rather than engage in a costly legal battle and as an added layer of protection, sellers and developers are taking matters into their own hands. Oftentimes, a seller will look to a separate set of restrictive covenants in which a prospective purchaser must contractually agree to hold the property as a rental property for a set number of years, which usually correlates with the remaining number of years for the statute of limitations on a construction defect claim to run in the state where the property is located. If properly executed, such covenants “run with the land”, meaning they subject the property itself, and not just the current or subsequent owners, to their terms and restrictions. However, in order to bind future owners of the property, restrictive covenants must first be publicly recorded in the county in which the property is located. Since the covenants will then become part of the “chain of title”, they will remain binding on successive purchasers, even if the new owner never informs the buyer that they exist.

Restrictive covenants have the potential added benefit of shielding contractors, subcontractors, and their respective insurers, from construction defect claims. For example, when an original builder constructs an apartment complex, it might understand that there is a reasonable potential the owner may bring a claim for construction defects. However, without a restrictive covenant, there is nothing to limit a subsequent owner from converting the apartments to condos, thereby exposing the original contractor to claims brought by unknown, unseen and unexpected future owners, homeowner's associations and the attorneys who thrive on prosecuting such claims. With the broad institution of restrictive covenants, this may provide some element of comfort to contractors, who oftentimes conduct risk assessment and underwrite potential legal costs into their estimates. Another added benefit of the reduced risk for construction defect claims is the potential for a reduction in costly insurance premiums, another potential benefit to contractors as well as the owners to whom they ultimately shift such added costs.

The Limits of Restrictive Covenants

While restrictive covenants may play an increasing role in today's multifamily market, sellers and developers should take special care in evaluating the risks and rewards of implementing mandatory restrictive covenants in a given transaction. Of particular note is the fact that the majority of condo conversions are taking place in older properties. For example, assuming the state where the property is located has an 8-year statute of limitations for actions arising from construction defects, if a property undergoes a condo conversion 10 years after it was originally built, then incorporating a restrictive covenant in such a transaction would provide little to no added benefit for a seller as the outside deadline to bring such a claim against the developer or builder has long since expired.

Another consideration is whether the institution of restrictive covenants will have an impact on the ability of a seller to sell the project. The existence of such restrictive covenants can have a significant impact on the value of a given property, since a buyer will be limited to maintaining the property for rental purposes for a given period of time, in lieu of the potential for a much wider profit to be gained from a condo conversion. For developers realizing considerable gains off the niche condo conversion market as an alternative to new construction, this may be a determining factor and a deal-breaker. As such, sellers and developers would be well-advised to thoroughly research their local market and the class of potential buyers, particularly when the demand for multifamily properties inevitably falls again, and the market becomes increasingly competitive.

Final Thoughts

While the decision to purchase real property evokes the consideration of many different elements, the trend of restrictive covenants on condo conversions is a practical reality in the negotiation of real estate transactions, and a growing one with which prospective purchasers will need to get comfortable. However, whether a condominium restrictive covenant is a benefit or a burden to a piece of real property is a matter of perspective, and will depend on the particular circumstances and purpose of the deal at hand.

Want to continue reading?

Become a Free ALM Digital Reader.

Once you are an ALM Digital Member, you’ll receive:

- Breaking commercial real estate news and analysis, on-site and via our newsletters and custom alerts

- Educational webcasts, white papers, and ebooks from industry thought leaders

- Critical coverage of the property casualty insurance and financial advisory markets on our other ALM sites, PropertyCasualty360 and ThinkAdvisor

Already have an account? Sign In Now

*May exclude premium content© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.