© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

Trending Stories

Events

- GlobeSt. Multifamily Spring 2025 April 01, 2025 - New YorkJoin the industry's top owners, investors, developers, brokers & financiers at THE MULTIFAMILY EVENT OF THE YEAR!More Information

- GlobeSt. Net Lease Spring 2025 April 01, 2025 - New YorkThis conference brings together the industry's most influential & knowledgeable real estate executives from the net lease sector.More Information

- Real EstateGlobeSt. ELITE Women of Influence (WOI) 2025July 21, 2025 - DenverGlobeSt. Women of Influence Conference celebrates the women who drive the commercial real estate industry forward.More Information

Recommended Stories

Influencers in CRE Technology 2025

By GlobeSt.com Staff | January 14, 2025

Here are our 2025 picks for tech influencers.

Newsom Waives CEQA to Speed Rebuild in SoCal Wildfire Areas

By Jack Rogers | January 14, 2025

The executive order directs HCD to facilitate a 30-day approval process for rebuild projects.

Robust Apartment Absorption Forecasted for 2025

By Erik Sherman | January 14, 2025

However, there are four potential headwinds on the horizon.

Resource Center

Assessment

Sponsored by Cherre

Data Management Scorecard: A Health Check for Your Data Management Capabilities and Challenges

CRE strategies and business decisions are only as strong as the data that powers them, and that data better be correct. This self-assessment will help you gauge your current data management capabilities.

Assessment

Sponsored by Cherre

Data Management Scorecard: A Health Check for Your Data Management Capabilities and Challenges

CRE strategies and business decisions are only as strong as the data that powers them, and that data better be correct. This self-assessment will help you gauge your current data management capabilities.

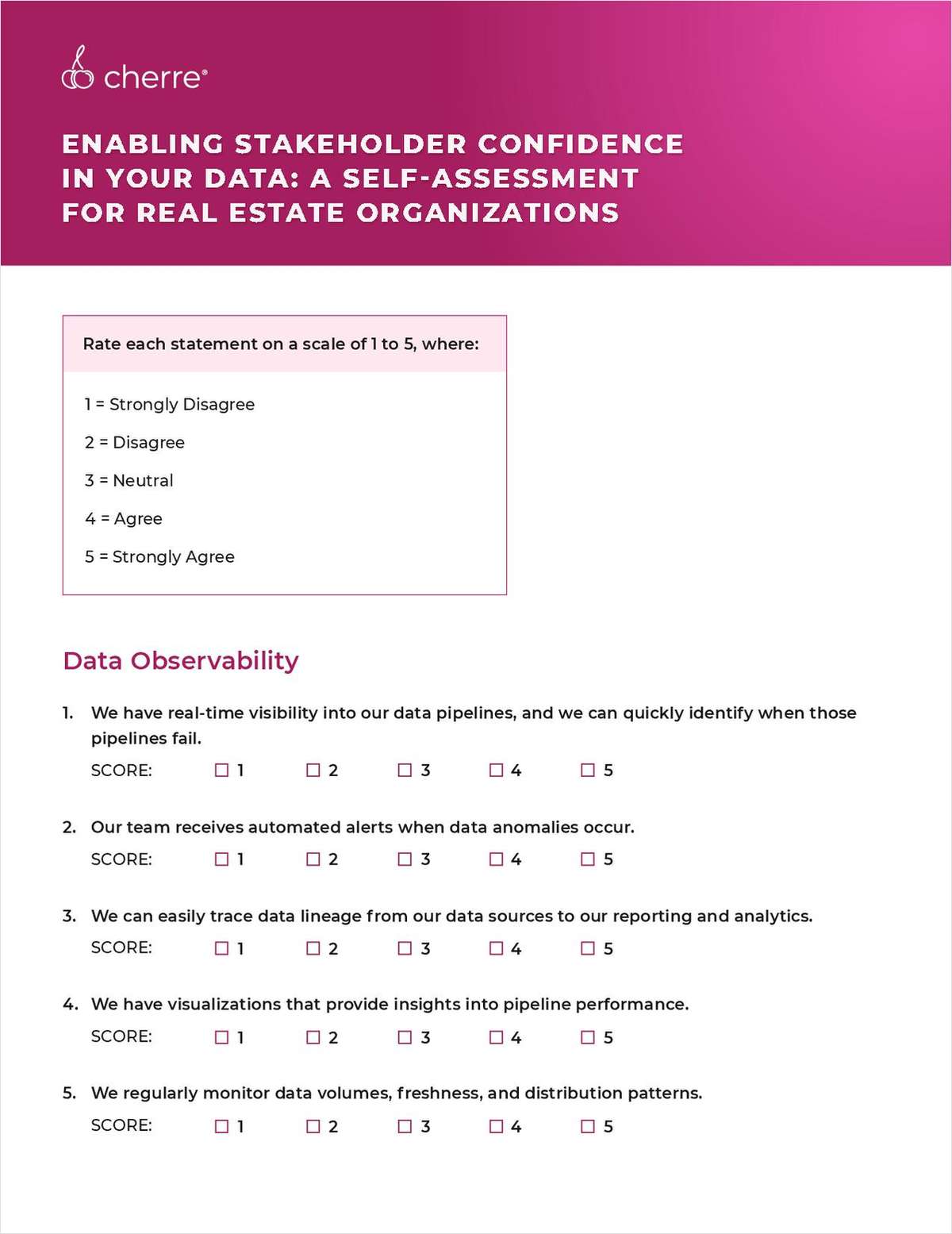

Assessment

Sponsored by Cherre

Enabling Stakeholder Confidence in Your Data: A Self-Assessment for Real Estate Organizations

Does your data inspire confidence or is there a significant lack of trust in its validity? Use this assessment to gauge where your organization’s data practices are at today and what gaps exist.